Robert Drew had been waiting for a crisis to film a President with his back to the wall. What he got in the summer of 1963 was not one, but two crises.

The first involved a standoff between President Kennedy and Governor George Wallace over the court-mandated integration of the all-white University of Alabama.

The second crisis was closer in, actually right in front of him. Time Inc. decided it no longer wanted to bankroll Drew Associates. Executives at Time Inc. had had a falling-out with ABC and now Time no longer had a national network outlet for the programs Drew Associates produced.

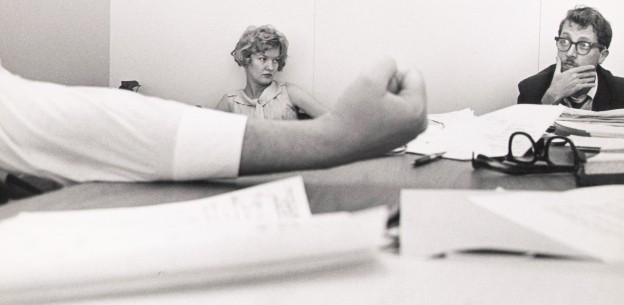

As money got tight, long-simmering tensions among Drew’s collaborators boiled to the surface. Richard Leacock and D.A. Pennebaker made it clear they were looking to leave, frustrated with Drew’s heavy-handed editing and his orders to produce more films, faster. Other staff members were told to go because there wasn’t enough production money to support what had grown to be an operation employing more than 80 people.

In the midst of upheaval, correspondent Greg Shuker read a story in The New York Times about two African-American students attempting to integrate the University of Alabama. Drew felt this would be the national crisis they had been waiting for. He got on the phone to Kennedy’s press secretary, Pierre Salinger, to get permission to film the administration’s response. Meanwhile, Shuker worked another angle. He took a copy of the prize-winning Drew Associates’ film “The Chair” and, communicating through a mutual friend, organized a screening for Robert Kennedy, JFK’s brother and the U.S. Attorney General, to view the film. Robert Kennedy loved it and kept the print to show the President. Drew’s relationship with Salinger and the President, coupled with Shuker’s end-run to the Attorney General paid off. They were in.

But, as Shuker recounts in P.J. O’Connell’s book, Robert Drew and the Development of Cinema Verite in America, there was a big problem: no money. “We had this remarkable movie that we were about to shoot and could not sell it going in, up front; the networks didn’t want to touch it,” Shuker said. “And so — I remember this quite vividly — we took, from Time, Inc., … what amounted to, as I remember it, like the last two months of the rent money, July and August rent money, and other overhead money — the phone and so forth — and physically put that money into buying raw stock and processing it. Gambling that we could sell that film after it was shot.”

The internal tensions at Drew Associates are not visible in the resulting film, “Crisis: Behind a Presidential Commitment,” which some consider Drew Associates’ finest film.

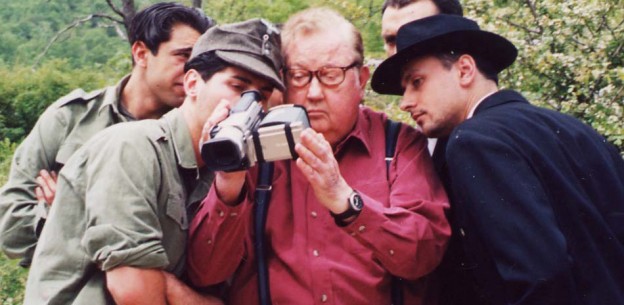

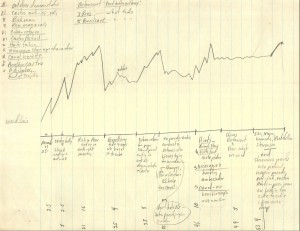

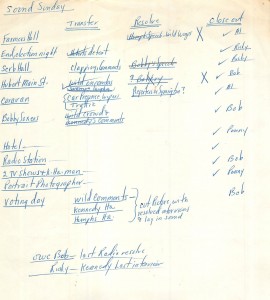

Drew assigned five teams including D.A. Pennebaker, Richard Leacock, James Lipscomb, Hope Ryden, Abbot Mills, headed by producer Gregory Shuker, to range from the Oval Office to the Justice Department to the University of Alabama.

As the crisis approached its climax, the Drew team was capturing the human details of a drama that would deeply affect the country, new civil rights legislation the President would like to have, and the Presidency itself. Using force on the Governor could destroy support Kennedy needed to further civil rights legislation. But allowing the Governor to block the students could set back the civil rights movement.

The remarkable filmmaking brings viewers into the Oval Office, as Robert Kennedy and various advisers cluster around President Kennedy, hammering out a strategy: Allow the Governor to turn back the students, then nationalize the Alabama National Guard and return for another try. Faced with his own guard, Gov. Wallace backed down. Vivian Malone walked into the university. That night on television, JFK made an historic commitment – the first president since Abraham Lincoln to commit the power of the presidency behind civil rights as a moral issue.

A great story, captured in a unique way — no other independent filmmaker had been inside the Oval Office recording as a president made decisions. Quite a scoop? Not everyone saw it that way. When The New York Times learned that Drew Associates’ cameras were in the Oval Office, its editorial page and its film reviewer were aghast. Before the film was finished and without having seen a single frame of the footage, The Times‘ editorial page inveighed against it: “The use of cameras could only denigrate the office of the President…. To eavesdrop on Executive decisions of serious Government matters while they are in progress is highly inappropriate. The White House isn’t Macy’s window.”

Out of money and out of time, Drew began planning to close down the company. But on July 30, ABC sent word that it would broadcast the program and Xerox Corp. stepped up as its sponsor. The film was saved. The company could pay its bills and live on.

A month before the scheduled broadcast, Drew faced one last test. As he had initially agreed, he allowed the Kennedys to see the film before it went on the air. In exchange for the access Drew Associates’ received, Drew had told the President’s people that if there were anything in the film that they believed would be damaging to the Presidency, he would address it. Although President Kennedy himself hadn’t seen the film, his people had some objections. Thus began a delicate dance that involved trips from New York to DC, re-writes of re-writes of narration, and many tense phones between Drew and Pierre Salinger, President Kennedy’s press secretary; Shuker and Ed Guthman, Robert Kennedy’s press secretary; Drew and Elmer Lower, president of ABC News.

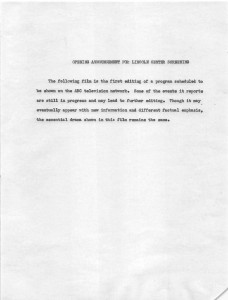

All agreed the film could be screened at the first New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center while their objections could be worked through; Drew wrote an announcement to accompany the screening, noting that it was still a rough cut. It read: “The following film is the first editing of a program scheduled to be shown on the ABC television network. Some of the events it reports are still in progress and may lead to further editing. Though it may eventually appear with new information and different factual emphasis, the essential drama shown in this film remains the same.”

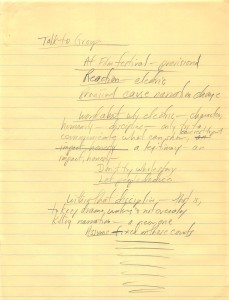

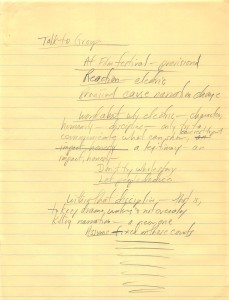

Drew wrote notes from which he apparently meant to report to others what happened at the New York Film Festival screening. The notes read:

“Talk to Group. At Film festival — provisional. Reaction — electric. Provisional cause narration change. Word about why electric — character, humanity — discipline — only try to communicate what can show, leave rest [illegible] — a legitimacy — and impact, honesty — Don’t try whole story. Let people deduce. Within that discipline — that is, to keep drama working and not overlay killing narration — a new one. Assume fixed on these counts.”

In early October, after President Kennedy had seen the film, final discussions led to an agreement: the Kennedys would drop their objections if Drew agreed to cover over most of the dialogue during the Oval Office meeting with a voice-over narration that would describe what was being discussed. This was a one-time-only requirement, however; every other time the film has screened all the Oval Office dialogue is audible and intact, just as it was at its premiere at the first New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center.

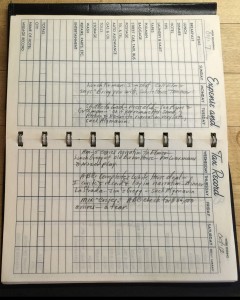

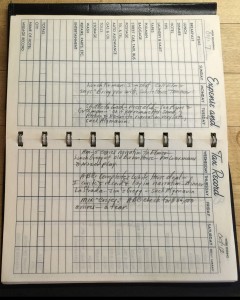

Another crisis averted. Drew describes some of the intense pressure he lived through in the week’s personal diary entries, a photo of which is below:

Monday: Lunch Firman. I’m shot. Call Elmer [Lower, president of ABC News]. “Bring your wits, White House tomorrow.”

Tuesday: Shuttle to Wash. — Press club [meet at National Press Club] — See Pierre [Salinger] and [Ed] Guthman — “ok if you remove Pres. sound.” Return & Re-write narration very late, sack Algonquin [Hotel].

Wednesday: A.M. — 5 copies narration to Elmber — Lunch Greg [Shuker] at Old Burbon House — P.M. [attend] Waxman’s and Nizer play.

Thursday: ABC completes White House deal — I write & record & lay in narration — dinner La Strada — Jim [Lipscomb] and Greg [Shuker] — sack Algonquin [Hotel].

Friday: Mix “Crises.” ABC check for $34,000 arrives — a tear.

The one-hour program, “Crisis: Behind a Presidential Commitment,” was broadcast by ABC on October 21, 1963. Reviewer John Horn of the New York Herald Tribune called the program, “An unprecedented television documentary that is a milestone in film journalism.” The Times reviewer, Jack Gould, could not get past his pique. “Mr. Drew’s program offered nothing new of legitimate public concern,” he wrote. Others disagreed. The film won several awards and was named to the Library of Congress National Film Registry.

As for Drew Associates, it did lose Pennebaker and Leacock, who struck out on their own and went on to make some of the most important documentaries of a generation. The remaining Drew Associates — Drew, Shuker, Ryden, Lipscomb, Mills — gathered forces to take their new journalism and apply it to the infinite forms and subjects and possibilities that lay ahead.