(Robert Drew wrote this description of making films after the severing of Drew Associates’ connection to Time, Inc.)

“Go make a film on the funeral.”

“What kind of film?”

“Your kind of film.”

That was the assignment from Elmer Lower, president of ABC News, as if we were talking about some event outside ourselves. But it was inside. Everyone was trying to control inner feelings.

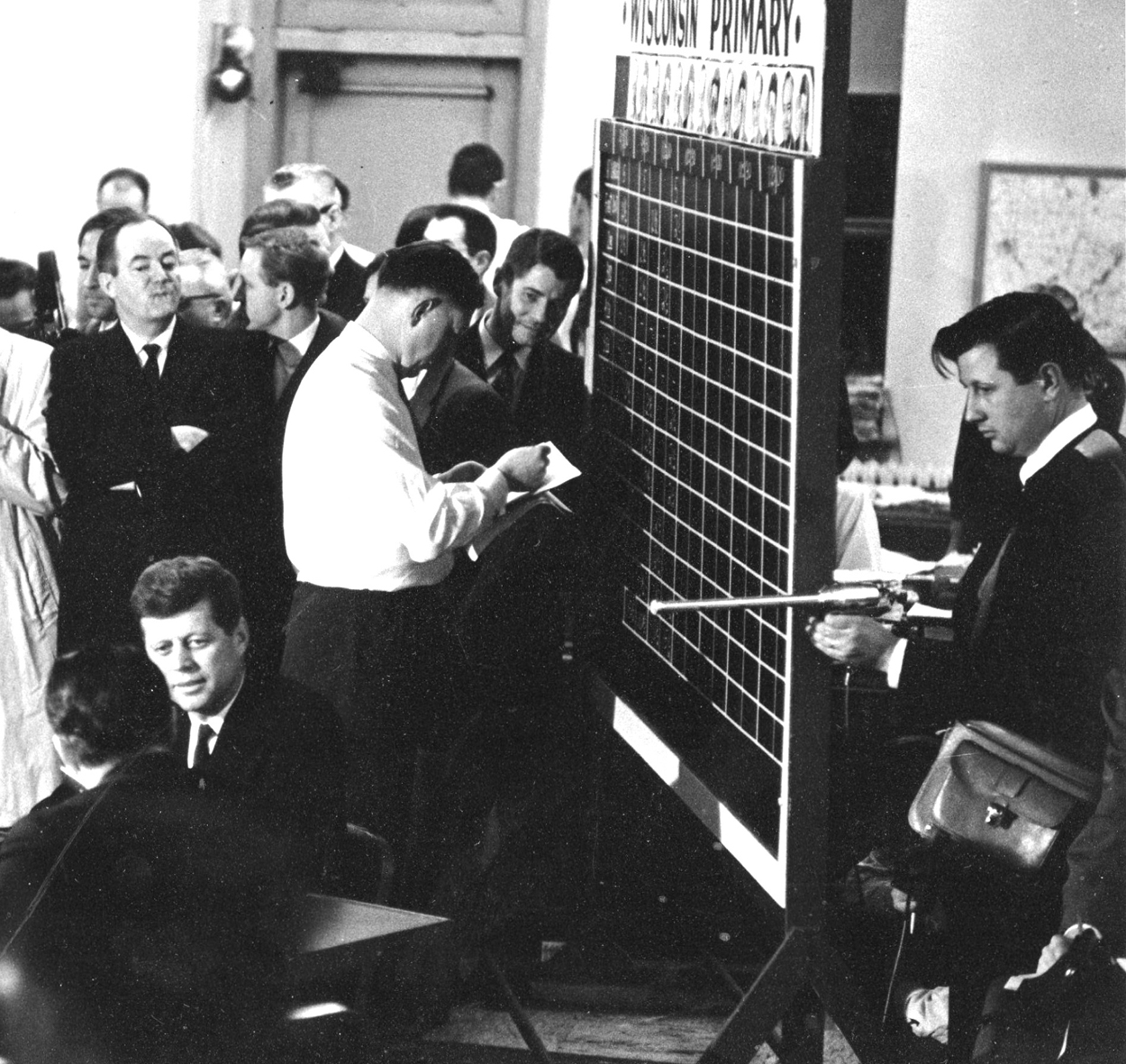

And that was the kind of film I made — photographed mainly by Jim Lipscomb — the onlookers and participants in Washington, DC that day, staring at the flag-draped casket of John F. Kennedy, watching the mournful parade, struggling to hide personal feelings that were so painfully revealed in their faces, the faces of November.

I also edited it my way, to the length it seemed to demand. That was 12 minutes, a non-television length. And with no narration. Juries at the Venice Film Festival gave it two first prizes. ABC could not cope with its odd length. It was not broadcast on American television until decades later.

—–

Although it asked for a film that it never aired, ABC nevertheless contracted Drew Associates for a new series of candid documentaries.

Drew was thrilled. This was the kind of assignment he had been seeking: a regular prime-time opportunity to air candid dramas. He believed that if viewers could get used to the kinds of films he made, they would prefer them not only to traditional documentaries, but also to fiction programs on entertainment television. He was seeking big audiences and felt personally invested in the mission to bring quality programming into every living room.

Drew still believed in the vision he honed back in 1954 when he was at Harvard on a Nieman fellowship. He knew there was a way to film real-life happenings and render them into art — the art of simplicity, the art of reality, which would be far more glorious than anything from the imagination.

He and his remaining Associates scoured the news looking for human dramas that would make good stories. Some subjects: a huge, young heavyweight boxer in Madison Square Garden, the Queen Elisabeth of the Belgians music competition, Phil Hill at Le Mans, a mission by two Peace Corps nurses in Malaysia. The series, called The Daring Americans, climaxed with the first major candid combat film, “Letters from Vietnam.”

While most of the films got good reviews and broad audiences, Drew’s fervent wish to change television as he knew it remained elusive. His films were still on the outer edges, not in the center of what was driving news or features on TV.

As it had begun, so it ended. The final film Drew Associates made for ABC was not broadcast by the network. “Storm Signal,” a film about drug addiction seen from inside a marriage, was not seen on television until Xerox Corp. itself syndicated the program by directly purchasing an hour of air time on syndicated stations across the country.

This time the falling-out came because ABC wanted more control over news-related programming. Lower offered Drew jobs for himself and his entire outfit, but they had to come into the ABC News fold proper. Drew declined. He was adamant that he would not join the network, which he sensed would have meant the death of his kind of filmmaking. So the two parted ways.