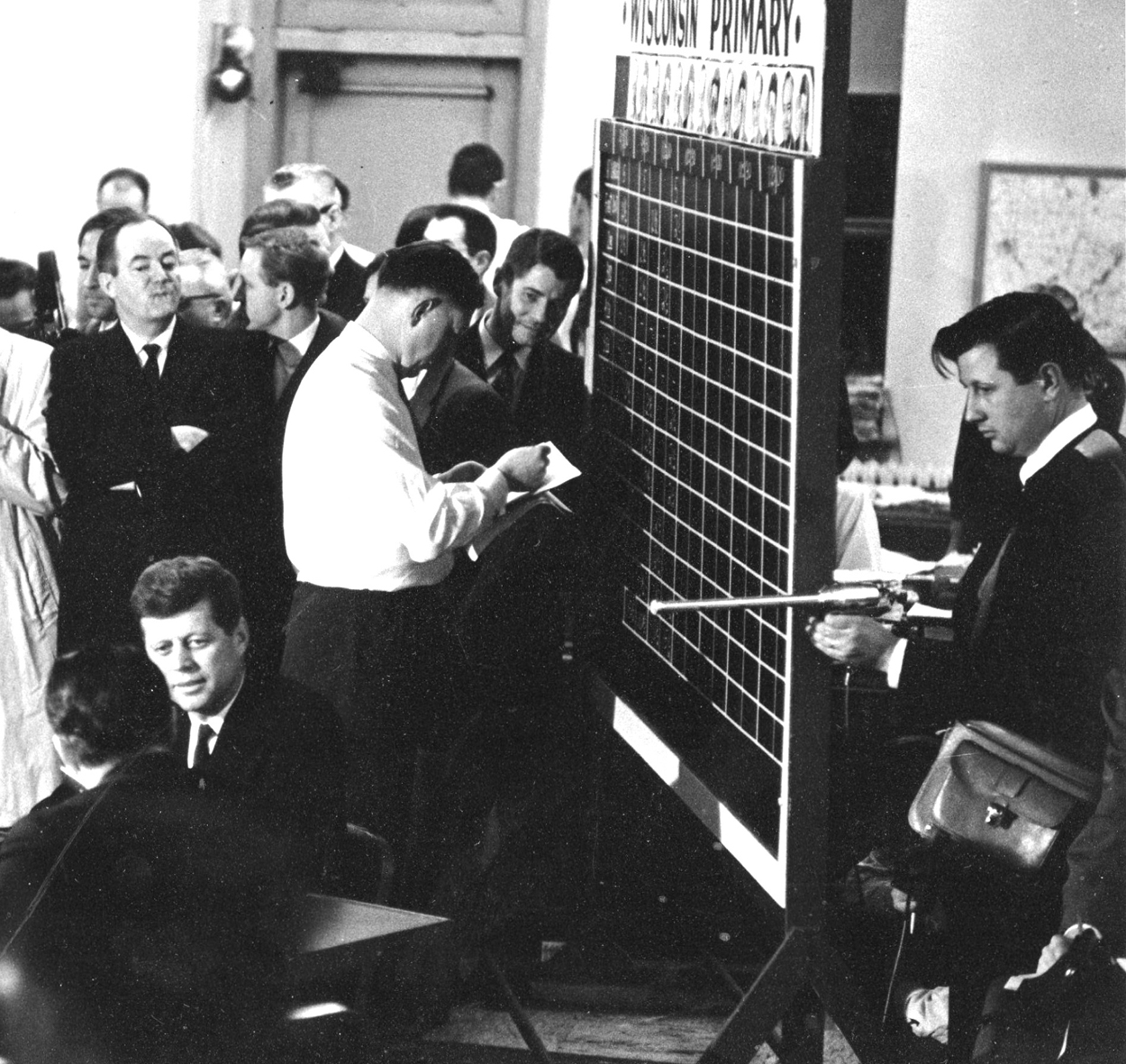

(In his booklet, this is how Robert Drew described the directions reality filmmaking took after “Primary.”)

After “Primary” came two proposals, the first from Time to film an automobile race in Indianapolis, where it owned a TV station, the second from ABC to film Latin America, “because CBS just did Africa.”

I resisted the race as too trivial and the continent as too sweeping. But “Primary” had pointed two directions for candid filmmaking to develop and Indianapolis and Latin America led those directions.

“Primary” combined the subject matter of documentary and the progression of drama. The next step could be for this kind of filmmaking to be seen as an addition to existing forms or as an original form in itself. But adding candidness to documentary would not change its basic purpose – to convey information – or its basic method – exposition. Candid Drama, however, would add a new purpose – to convey, movie-like, strong experience – and a new method – story-telling through real characters in action. Drama and Documentary. Experience and Exposition. Indianapolis and Latin America.

At the Indianapolis race track I heard a driver telling how he turned a corner. He spoke with such passion that it raised hairs on the back of my neck. Eddie Sachs had driven faster than any other qualifier and would begin the race from the front row, inside – on the pole. Eddie was so excited that he could hardly control himself.

To me the race suddenly became untrivial. When Eddie led the pack roaring through the start, I had five cameras rolling. Eddie came within an ace of winning the race, then suffered a mechanical failure. Leacock and I were with him as he wandered dazed, waving at a crowd that was ignoring him. “Next year, Eddie,” his wife said.

The next year he again led and lost and the next he died in a fiery collision. When “On The Pole” opened a program of our films in a theatre in Paris, the top ten critics there rated it above all Hollywood films of that season.

Then came “Yanki No!” I protested that I could “do” a continent only if I found characters caught up in a story that would reveal a great deal about that continent. Then a story materialized.

At a meeting in Costa Rica, the U.S. would force the expulsion of Cuba from the Organization of American States. Latin America would then explode with protests. In Havana, Fidel Castro would whip a crowd of a million into a frenzy. I imagined mobs charging the camera shouting, “Yanki No!”

A week later in Caracas they were doing just that and Ricky and I, on the scene, were grateful to be able to duck into a parked car. But by combining candid humanity with documentary exposition, we were able to allow the actions of diplomats, slum dwellers and protesters to drive home the problems and attitudes confronting the U.S. south of its border.

Yanki No! was praised right and left.

ABC contracted for more documentaries. Now I would have the opportunity to produce a candid series.

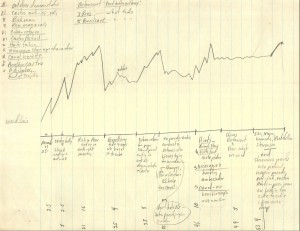

(A hand-drawn graphic Drew used to plan out how to edit the footage for Yanki No! into a narrative. Drew and his yellow legal pads became legendary at Drew Associates. Drew insisted on screening all daily rushes of all films in production and he scribbled copious notes onto yellow legal pads. He carried these writing pads with him on the train [he commuted into New York City from his home in Darien, Connecticut] and often worked out strategic issues by drawing graphics.)