When Governor George Wallace literally stands in the schoolhouse door to block the admittance of two African-American students to the all-white University of Alabama in June 1963, President Kennedy is forced to decide whether to use the power of the presidency to back racial equality.

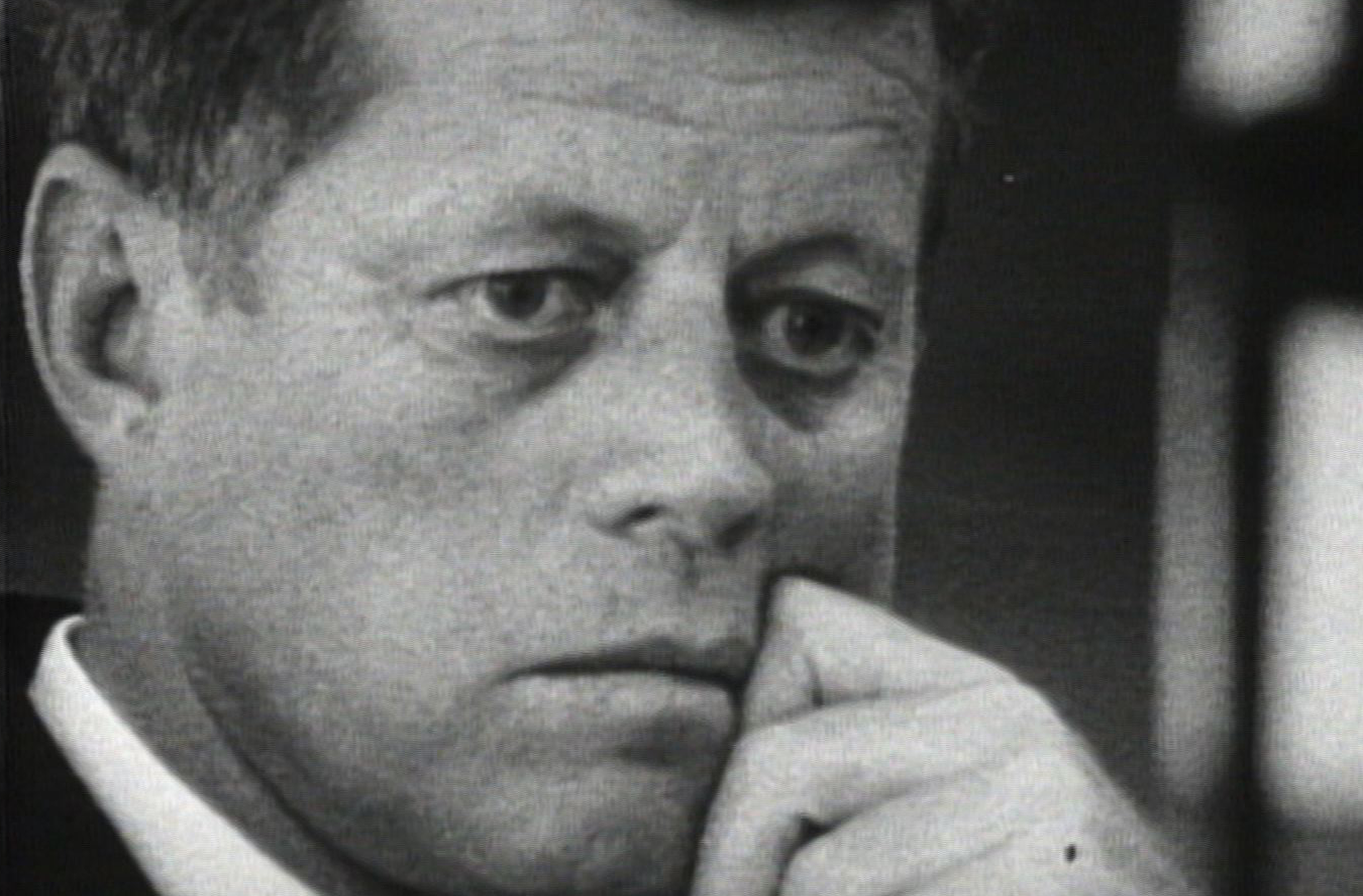

“Crisis” captures events from all sides, using the cinema verite techniques pioneered by Drew Associates. The cameras follow the President, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, Wallace, and the two students, Vivian Malone and James Hood, as the crisis unfolds and up through its dramatic climax, including rare scenes of decision-making inside the Oval Office.

The film delivers on its promise to show history in the making, and not just in the grand gestures and grim strategy sessions that dominate the action. The filmmakers also capture small, human moments. One of the most delightful scenes in the film starts out as an important telephone conversation between RFK in his office at the Justice Department in Washington, DC and his deputy on the scene in Alabama, Nicholas Katzenbach. The scene intercuts between both ends of the conversation — the Washington end being filmed by D.A. Pennebaker and the Alabama end by Richard Leacock. Neither cameraman knew if the other were filming at the time. One of RFK’s young daughters, who is visiting her dad at work, wanders to her father’s knee. Kennedy gives her the phone as he tells Katzenbach, “Want to say hi to Kerry?” Flash to Alabama, where Katzenbach’s serious stare softens with delight as he chats with his young friend. Leacock later described finding those two pieces of simultaneous recording as one of the most exciting moments of his filmmaking career.

And on the substance of racial integration, the filmmakers convey the sense of how dangerous the situation actually was for students Malone and Hood. There is a quiet bravery and steely resolve in Malone’s demeanor; Hood jokes that he won’t stop with being admitted to the university. He will push all the way until he is elected governor of the state – a feat that then seemed like a far-away fantasy.

The film was controversial in journalistic circles at the time. When The New York Times got wind that there was an independent documentary filmmaker with a camera inside the Oval Office, it wrote a blistering editorial against the privileged access, scolding the Kennedys that the White House was not “Macy’s window,” where onlookers could gawk. “The use of cameras could only denigrate the office of the President. The propagandistic connotations of this filming is unavoidable.”

Of course, if it had been The Times that had that access, the newspaper’s feelings might have been different. Indeed, in later years, The Times’ reporters and critics praised the film. Alessandra Stanley, in a 2003 article in The Times’ Arts section, called “Crisis” “an astonishingly intimate look at Kennedy and his brother…. The politics and personalities remain fascinating, and so does the filmmaking.”

But in 1963, its film critic, Jack Gould, not only failed to recognize the filming as a cinematic breakthrough, he was blunt about his dislike: “Robert Drew, producer of the program, achieved a formidable coup: his presentation surely will stand as a prime example of governmental surrender to the ceaseless and often thoughtless demands of the entertainment world.”